THE ALMANACK

THE INSPIRATION

Fortunately, as a historical novelist, I love to research the past. My first intention was to explore the lost world of historical almanacks, planning to write the novel so that the reader "can only surmise that the author had such a real document in her hands at the time of writing." (Jan Lambert). My first surprise was that this did not involve long hours in the British Museum. Many old documents, including a good array of 1752 almanacks are available online, having been digitised by universities and libraries. I was also delighted to buy an 1801 edition of Old Moore’s Vox Stellarum for £20 on eBay – a bargain, I believe.

I soon discovered that the better sorts of almanacks featured rhyming riddles of various types: enigmas, rebuses, conundrums and acrostics. I love a good puzzle and on the next page I write about the ‘riddlemania’ that gripped Georgian society, provoking wits from Jane Austen to Jonathan Swift to compose examples.

Finally, there is only so much book research a person can do. I enjoy getting away from the computer and looking for traces of the past in the real world. Overleaf. I write about a visit to the location of the BBC’s Victorian Farm and my thoughts on time, nature and the night sky, as I wrote The Almanack.

I soon discovered that the better sorts of almanacks featured rhyming riddles of various types: enigmas, rebuses, conundrums and acrostics. I love a good puzzle and on the next page I write about the ‘riddlemania’ that gripped Georgian society, provoking wits from Jane Austen to Jonathan Swift to compose examples.

Finally, there is only so much book research a person can do. I enjoy getting away from the computer and looking for traces of the past in the real world. Overleaf. I write about a visit to the location of the BBC’s Victorian Farm and my thoughts on time, nature and the night sky, as I wrote The Almanack.

historical almanacks

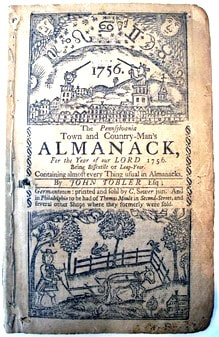

For some years I had wanted to write a murder mystery set in an English village; it was the discovery of almanacks that inspired me to get started. Almanacks were little pocket-sized booklets combining calendars, astronomical observations, and predictions. They were read by many people who read little else, and offer many insights into our ancestors lives – the care of crops and livestock, herbal remedies, weather lore, and even lucky and unlucky times to travel or cut one’s hair. The astronomical information was used to plant crops and plan the day and night's tasks. Before use of electricity the moon was a crucial factor in night-time journeys and people without clocks learned to tell the time using the stars.

For centuries almanacks were an essential part of everyday life and at times outsold even the Bible. There was an almanac for almost every taste and town; during the seventeenth century over two thousand different almanacs were published. In the Georgian era the leading almanack in England was Old Moore’s, in spite of the astrologer Francis Moore having died in 1714 - a drawback ignored to this day.

For centuries almanacks were an essential part of everyday life and at times outsold even the Bible. There was an almanac for almost every taste and town; during the seventeenth century over two thousand different almanacs were published. In the Georgian era the leading almanack in England was Old Moore’s, in spite of the astrologer Francis Moore having died in 1714 - a drawback ignored to this day.

PREDICTIONS

The popularity of almanacks was in part due to their astrological predictions. Chapbooks and almanacks had long suggested it was possible to see into the future, by way of weather lore, dream books, ghost stories, or fortune-telling. My novel asks what might happen if an almanack appeared to predict a series of murders around the traditional year in an English village. There is a very human fascination with jumping time to glimpse the future, by means of divination, dream books, ghost stories, and aids to prognostication such as my facsimile 17th century fortune-telling cards pictured below. I wondered how these prophecies would fare today?

The popularity of almanacks was in part due to their astrological predictions. Chapbooks and almanacks had long suggested it was possible to see into the future, by way of weather lore, dream books, ghost stories, or fortune-telling. My novel asks what might happen if an almanack appeared to predict a series of murders around the traditional year in an English village. There is a very human fascination with jumping time to glimpse the future, by means of divination, dream books, ghost stories, and aids to prognostication such as my facsimile 17th century fortune-telling cards pictured below. I wondered how these prophecies would fare today?

Some predictions were self-evidently accurate, such as January’s unsurprising weather forecast, ‘Cold Air and some Frost.’ Other Astrological Observations used intentionally vague ‘Barnum statements’, such as ‘matters of great moment are near agitation,’ or truisms like ‘Fevers at this time of year send some to become Shades’.

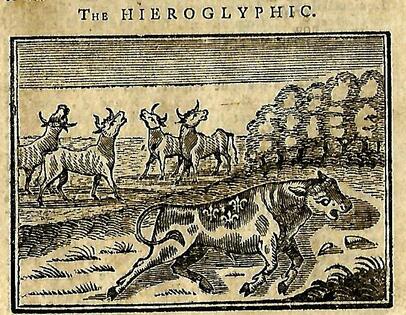

Each year, Moore’s printed its eagerly awaited Hieroglyphic, a symbolic picture suggesting the ‘state of the nations’. In my 1801 Vox Stellarum the image of an injured bull bearing a fleur-de-lis is recognisably a reference to France. October’s motto reads: “Peace is sought by those who Peace invade.” I expected to scoff, but history proves that on 1 October 1801 the preliminary peace agreement between Britain and France was indeed published.

Towards the end of the 18th century moves were made to outlaw fortune-telling. Australian academic Maureen Perkins finds this sinister: “Visions of the future were a threat to the scientific might of industrial society based on the regularity of the clock.” She makes the interesting claim that denying such recreational manipulation of different futures may well be to civilisation’s cost, in a lack of wonder, imagination, and readiness for change.

the loss of 11 days

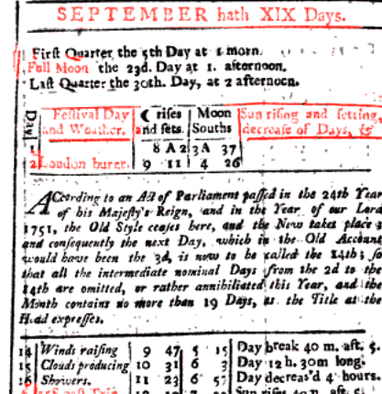

Before 1752 a gap of 11 days existed between Britain’s Julian calendar and much of Europe, which had moved to the Gregorian system. Not only had Britain’s calendar drifted out of kilter with the solar year, but Brexit-like confusion reigned over European trade due to the two parallel dating systems. Thus the Calendar Act of 1752 announced the ‘annihilation of eleven days’ whereby Britons went to bed on Wednesday the second of September and woke up on Thursday the fourteenth.

It is a myth that riots took place, but anxiety about the change can be traced in diaries and journals, comparable to the year 2000 ‘millennium bug’. People lost their birthdays, pay days, and in my home town of Chester confusion about the mayor’s election needed an act of parliament to set it right. All this felt like a wonderful basis for a crime novel, where I could sow seeds of confusion amongst the inhabitants of my fictional village of Netherlea.

It is a myth that riots took place, but anxiety about the change can be traced in diaries and journals, comparable to the year 2000 ‘millennium bug’. People lost their birthdays, pay days, and in my home town of Chester confusion about the mayor’s election needed an act of parliament to set it right. All this felt like a wonderful basis for a crime novel, where I could sow seeds of confusion amongst the inhabitants of my fictional village of Netherlea.

There is a persuasive theory that the calendar change disrupted the ‘natural time’ that had always followed the sun and moon, seasons and crops. As the elite of Georgian society endeavoured to regulate time – by way of clocks, machines, laws and eventually the factory whistle – resistance to the New Style calendar survived in almanacks, many of which chose to print the Old and New Styles for the remainder of the century.

When the calendar changed, putting back traditional feasts by 11 days gave practical consequences. For example, there was resistance to the October Michaelmas feast being postponed because the traditional geese were not yet fat enough to feast upon. Similarly, it is far less likely to snow in Britain on the New Style Christmas Day than on the old feast day, which once fell on 6 January. It is intriguing that we continue to picture Christmas with a snowy landscape. Perhaps we still have a folk memory of the older calendar?

When the calendar changed, putting back traditional feasts by 11 days gave practical consequences. For example, there was resistance to the October Michaelmas feast being postponed because the traditional geese were not yet fat enough to feast upon. Similarly, it is far less likely to snow in Britain on the New Style Christmas Day than on the old feast day, which once fell on 6 January. It is intriguing that we continue to picture Christmas with a snowy landscape. Perhaps we still have a folk memory of the older calendar?

Read on here to find out more about riddles and research.

Copyright © 2015